FEATURE:

Oh! You Pretty Things

IN THIS PHOTO: David Bowie in 1971/PHOTO CREDIT: Brian Ward

Ten of the Best Albums from 1971

___________

I am returning to the year 1971…

IN THIS PHOTO: Joni Mitchell

for a couple of reasons. For one, there is a new Apple docuseries, 1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything, that I will get to soon. One titanic and hugely important album from 1971, Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, has just turned fifty. Another, Joni Mitchell’s Blue, is fifty on 22nd June. Some would argue 1971 is the finest year ever for music. Whilst I think that honour goes to 1994, one marvels at the variety of genius albums released in 1971 and how important and timeless they are! So busy and eclectic, it must have been thrilling for music lovers in 1971. Not to be reductive, but I want to highlight ten terrific albums from 1971 that adds to the argument that it is one of the greatest years for music. I am looking forward to Joni Mitchell’s Blue turning fifty. There are many other rich and hugely popular albums that hit that anniversary later in the year. Before coming to a top-ten, The Guardian published a feature recently regarding the new Apple docuseries. They highlight the joys of the series and a few of the albums under the microscope:

“Volume is paramount on the new Apple docuseries 1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything, both in the play-it-loud sense as well as the sheer-quantity sense. The watershed social and artistic moment explored across the eight episodes contained a staggering amount of genius, to the point that an interview quickly dissolves into the same awed name-cataloguing one might expect to hear around a college radio station or independent record shop.

“It’s a predictable answer,” executive producer James Gay-Rees tells the Guardian, “but my favorite is What’s Going On, really one of the greatest songs of all time.”

“We bought all the discussed records on vinyl, listened to them fully through as cohesive works, and at different times, different ones became my favorite,” explains episode director James Rogan. “I had a phase with Hunky Dory, one with Bill Withers’ Just As I Am. As single songs go, What’s Going On was massive for me as well.”

“We can’t get into a chat without the words Sly Stone,” pipes in full-series director Asif Kapadia, an Oscar-winner for his 2015 bio-doc on Amy Winehouse. “Curtis Mayfield, too. Isaac Hayes, with the theme from Shaft.”

“Gil Scott-Heron, Pieces of a Man.”

“Aretha Franklin’s recording of Bridge Over Troubled Water.”

“Tapestry, by Carole King.”

It’s easy to imagine them continuing this for several hours, probably with a case of beers and a good set of speakers.

But for all their open-hearted admiration, the brilliance of their new project lies in the discipline with which they channel that spirit of fandom into a more studied form of cultural anthropology. The vast purview of their chosen year – John Lennon moving to New York, the Stones shacking up in the south of France, the Concert for Bangladesh, Joni Mitchell releasing Blue, the list of key events seems to go on forever – forced them to consider more thoughtful, creative methods of organizing the material. Though they worked from the basis of David Hepworth’s book Never a Dull Moment, the creative team wanted to move away from his straightforward chronology toward a structure shaped by overarching themes.

IN THIS PHOTO: Marvin Gaye

The series eschews the usual talking-head interview segments, instead jam-packing every episode with archival filmstrips from front to back. Snippets of disembodied voiceover blur the line between the excavated audio from the period and the soundbites the directors harvested themselves in the present day. As Kapadia would have it, the cohering effect was intentional. “We’ve been making archive-driven films for a while now, and the whole idea is to make everything feel like part of the same universe,” he says. “You shouldn’t be able to mark them, ‘Oh, that’s a period sample, and oh, that’s a contemporary one.’ The whole thing should be in the moment, 1971 as the present. We don’t cut from people now, older, to their younger beautiful selves. The whole thing is about being there, walking down the street in 1971”.

Others may have their own opinions as to the ten best albums of 1971. It is so tough to narrow it down, though I think the albums below are among the very finest. They are tremendously important and engaging albums that I think will survive for decades and move people very many years from now. Despite the fact that I truly believe 1994 was the best year for music/albums, exploring the very best of 1971 has given me…

IN THIS PHOTO: Led Zeppelin/PHOTO CREDIT: Michael Ochs Archive

PAUSE for thought.

_______________

David Bowie - Hunky Dory

Release Date: 17th December

Label: RCA

Producers: Ken Scott/David Bowie

Standout Tracks: Oh! You Pretty Things/Life on Mars?/Kooks

Review:

“The theme of shifting sexual identity became the core of Bowie's next album, 1971's scattered but splendid Hunky Dory: "Gotta make way for the Homo Superior," he squeals on the gay-bar singalong "Oh! You Pretty Things", simultaneously nodding to Nietzsche and to X-Men. He'd also made huge leaps as a songwriter, and his new songs demonstrated the breadth of his power: the epic Jacques Brel-gone-Dada torch song "Life on Mars?" is immediately followed by "Kooks", an adorable lullaby for his infant son. The band (with Trevor Bolder replacing Visconti on bass) mostly keeps its power in check—"Changes" is effectively Bowie explaining his aesthetic to fans of the Carpenters. Still, they cut loose on the album's most brilliant jewel, "Queen Bitch", a furiously rocking theatrical miniature (Bowie-the-character-actor has rarely chewed the scenery harder) that out-Velvet Undergrounds the Velvet Underground” – Pitchfork

Key Cut: Changes

Marvin Gaye – What’s Going On

Release Date: 21st May

Label: Tamla

Producer: Marvin Gaye

Standout Tracks: Save the Children/Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)/Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)

Review:

“Conceived as a statement from the viewpoint of a Vietnam veteran (Gaye's brother Frankie had returned from a three-year hitch in 1967), What's Going On isn't just the question of a baffled soldier returning home to a strange place, but a promise that listeners would be informed by what they heard (that missing question mark in the title certainly wasn't a typo). Instead of releasing listeners from their troubles, as so many of his singles had in the past, Gaye used the album to reflect on the climate of the early '70s, rife with civil unrest, drug abuse, abandoned children, and the spectre of riots in the near past. Alternately depressed and hopeful, angry and jubilant, Gaye saved the most sublime, deeply inspired performances of his career for "Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)," "Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)," and "Save the Children." The songs and performances, however, furnished only half of a revolution; little could've been accomplished with the Motown sound of previous Marvin Gaye hits like "Stubborn Kind of Fellow" and "Hitch Hike" or even "I Heard It Through the Grapevine." What's Going On, as he conceived and produced it, was like no other record heard before it: languid, dark, and jazzy, a series of relaxed grooves with a heavy bottom, filled by thick basslines along with bongos, conga, and other percussion. Fortunately, this aesthetic fit in perfectly with the style of longtime Motown session men like bassist James Jamerson and guitarist Joe Messina. When the Funk Brothers were, for once, allowed the opportunity to work in relaxed, open proceedings, they produced the best work of their careers (and indeed, they recognized its importance before any of the Motown executives). Bob Babbitt's playing on "Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)" functions as the low-end foundation but also its melodic hook, while an improvisatory jam by Eli Fountain on alto sax furnished the album's opening flourish. (Much credit goes to Gaye himself for seizing on these often tossed-off lines as precious; indeed, he spent more time down in the Snakepit than he did in the control room.) Just as he'd hoped it would be, What's Going On was Marvin Gaye's masterwork, the most perfect expression of an artist's hope, anger, and concern ever recorded” – AllMusic

Key Cut: What’s Going On

Joni Mitchell - Blue

Release Date: 22nd June

Label: Reprise

Producer: Joni Mitchell

Standout Tracks: Blue/California/A Case of You

Review:

“All I Want," though it begins the album, marks the end of the long holiday journey described in "Carey" and "California." Both songs have the syncopated, Latin touch that characterizes the best cuts on the album. "Carey," a calypso about dalliance on Crete, had a definite festival flavor, but with a twist at the end: "The wind is in from Africa/Last night I couldn't sleep/Oh, you know it sure is hard to leave here but it's really not my home."

"California" jumps along in short bursts, the lyrics giving snapshots of Joni's European itinerary. Then comes the flowing chorus with its hint of tango, its plaintive pedal steel guitar and its homesick refrain: "Oh, it gets so lonely/When you're walking and the streets are full of strangers." The song is a model of subtle production; James Taylor's twitchy guitar and Russ Kunkel's superb, barely detectable high-hat and bass-pedal work give it just the right amount of propulsion.

In "This Flight Tonight," "A Case of You," and "Blue," Joni comes to terms with the reality that loneliness is not simply the result of prolonged traveling; the basic problem is that her lover will not give her all she wants. In "This Flight Tonight," Joni has walked out on her man, is flying West on a jet, and now regrets the decision. The lyrics, a clumsy attempt at stream of consciousness, are virtually unsingable and Joni's lyric soprano is hopelessly at odds with the rock and roll tune. But the chorus has just the wispiest trace of Bo Diddley and it sticks with you:

Oh Starbright, starbright

You've got the lovin' that I like, all right

Turn this crazy bird around

I shouldn't have got on this flight tonight.

In "A Case of You," James repeats the same dotted guitar riff he played in "California," only the melody here is slow, stately and almost hymnlike. The song is neatly divided in its ambivalence: each verse is about a setback to the affair, followed by a chorus in which Joni affirms: "But you are in my blood like holy wine." In comparing love to communion, Joni defines explicitly the underlying theme of Blue: for her love has become a religious quest, and surrendering to loneliness a sin.

It is only a short step from that to Joni's vow that she will walk through hell-fire to follow her man: "Well everybody's saying/That hell's the hippest way to go/Well I don't think so/But I'm gonna look around it though/Blue I love you." This is "Blue," the last cut on the first side but clearly the album's final statement, the bottom of the slope downward from the euphoria of "All I Want." For all its personal revelation, "All I Want" still sounds like a beautiful pop tune; "Blue," on the other hand, has the secret, ineffably sad feeling of a Billie Holliday song. Joy, after all, can be shared with everybody, but intense pain leads to withdrawal and isolation.

"Blue" is a distillation of pain and is therefore the most private of Joni's private songs. She wrote it for nobody but herself and her lover:

Blue here is a shell for you

Inside you'll hear a sigh

A foggy lullaby

There is your song from me.

The beauty of the mysterious and unresolved melody and the expressiveness of the vocal make this song accessible to a general audience. But "Blue," more than any of the other songs, shows Joni to be twice vulnerable: not only is she in pain as a private person, but her calling as an artist commands her to express her despair musically and reveal to an audience of record-buyers:

And yet, despite the title song. Blue is overall the freest, brightest, most cheerfully rhythmic album Joni has yet released. But the change in mood does not mean that Joni's commitment to her own very personal naturalistic style has diminished. More than ever, Joni risks using details that might be construed as trivial in order to paint a vivid self portrait. She refuses to mask her real face behind imagery, as her fellow autobiographers James Taylor and Cat Stevens sometimes do.

In portraying herself so starkly, she has risked the ridiculous to achieve the sublime. The results though are seldom ridiculous; on Blue she has matched her popular music skills with the purity and honesty of what was once called folk music and through the blend she has given us some of the most beautiful moments in recent popular music. (RS 88)” – Rolling Stone

Key Cut: Carey

The Rolling Stones - Sticky Fingers

Release Date: 23rd April

Label: Polydor

Producer: Jimmy Miller

Standout Tracks: Wild Horses/Can't You Hear Me Knocking/Sister Morphine

Review:

“In the topsy-turvy world of success they’d had more than their share of recent ups and downs. Sticky Fingers was destined to be the triumphant first release from their self-owned label but this success was leavened by the fact that they’d signed over their back catalogue to previous manager Allen Klein and had to give him the royalties from Brown Sugar and Sway to boot. The incessant touring meant that the band were now world citizens, but they still moved closer to their American roots. Using the usual support cast of Bobby Keys, Ry Cooder and Nicky Hopkins they turned their experiences into ten tracks of narcotic misery and sexual frustration. All wrapped in a very louche Andy Warhol sleeve.

Narcotics are a major theme, of course, but also loss, frustration and incredible world-weariness. Reviews at the time complained that Sticky Fingers lacked the bite of previous releases like Let It Bleed or Beggars Banquet, but it’s this very quality that makes the album special. Like Neil Young’s Tonight’s the Night, the sense of a wake creeps through tracks like Dead Flowers and Sister Morphine.

Elsewhere, the Delta serves as a touchstone for some of Jagger’s most heartfelt wailing as on I Got the Blues and You’ve Gotta Move, while he’s never bettered his letchery on Brown Sugar. Taylor’s arrival is keenly felt on Can’t You Hear Me Knocking?, with its Santana-esque coda. Sway and Bitch are hard-bitten rockers that couldn’t exist without Charlie’s taut snare.

Eventually the whole thing collapses in on itself with Moonlight Mile. A coked-out, somnambulant drift through an era’s last days, and a beautiful end to a beautiful journey. While many hold their next album, Exile On Main St., as their zenith, Sticky Fingers, balancing on the knife edge between the 60s and 70s, remains their most coherent statement” – BBC

Key Cut: Brown Sugar

Led Zeppelin - Led Zeppelin IV

Release Date: 8th November

Label: Atlantic

Producer: Jimmy Page

Standout Tracks: Black Dog/Rock and Roll/When the Levee Breaks

Review:

“One of the ways in which this is demonstrated is the sheer variety of the album: out of eight cuts, there isn’t one that steps on another’s toes, that tries to do too much all at once. There are Olde Englishe ballads (“The Battle of Evermore” with a lovely performance by Sandy Denny), a kind of pseudo-blues just to keep in touch (“Four Sticks”), a pair of authentic Zeppelinania (“Black Dog” and “Misty Mountain Hop”), some stuff that I might actually call shy and poetic if it didn’t carry itself off so well (“Stairway to Heaven” and “Going To California”) …

… and a couple of songs that when all is said and done, will probably be right up there in the gold-starred hierarchy of put ’em on and play ’em again. The first, coyly titled “Rock And Roll,” is the Zeppelin’s slightly-late attempt at tribute to the mother of us all, but here it’s definitely a case of better late than never. This sonuvabitch moves, with Plant musing vocally on how “It’s been a long, lonely lonely time” since last he rock & rolled, the rhythm section soaring underneath. Page strides up to take a nice lead during the break, one of the all-too-few times he flashes his guitar prowess during the record, and its note-for-note simplicity says a lot for the ways in which he’s come of age over the past couple of years.

The end of the album is saved for “When The Levee Breaks,” strangely credited to all the members of the band plus Memphis Minnie, and it’s a dazzler. Basing themselves around one honey of a chord progression, the group constructs an air of tunnel-long depth, full of stunning resolves and a majesty that sets up as a perfect climax. Led Zep have had a lot of imitators over the past few years, but it takes cuts like this to show that most of them have only picked up the style, lacking any real knowledge of the meat underneath.

Uh huh, they got it down all right. And since the latest issue of Cashbox noted that this ‘un was a gold disc on its first day of release, I guess they’re about to nicely keep it up. Not bad for a pack of Limey lemon squeezers” – Rolling Stone

Key Cut: Stairway to Heaven

Carole King – Tapestry

Release Date: 10th February

Labels: Ode/A&M

Producer: Lou Adler

Standout Tracks: I Feel the Earth Move/Will You Love Me Tomorrow?/(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman

Review:

“She was 19 when “Will You Love Me Tomorrow?” first came out; she wrote the music, arranged the strings using a book on orchestration borrowed from the public library, and played piano on the recording. The lyric was a kind of response to the Shirelles’ previous hit, “Tonight’s the Night,” but turned “sideways and upside down,” King has said. For 1960, it was rather radical: the voice of a clear-eyed young woman accepting the possibility of a one-night stand—“Can I believe the magic in your sighs?”—despite her longing for true love, resigned but not fooled. It became the first No. 1 hit of the girl group era. King and Goffin were so proud of the song that they engineered the doorbell of their home in suburban New Jersey to play its lovelorn hook every time a visitor arrived. But perhaps it was a cautionary tale for their own doomed marriage. On Tapestry, “Will You Love Me Tomorrow?” was a raw emblem of King’s own complex teenage years, and she sang it in careful measures, as if savoring the memory in each note.

King and Goffin wrote their monumental Aretha single after Atlantic exec Jerry Wexler pulled up to them while walking on Broadway, rolled down the window of his limo, and asked them to craft a hit for her with the title “Natural Woman.” They drove home to New Jersey, listened to R&B and gospel on the Black-programmed WNJR, and poured out a piece of history: “When my soul was in the lost and found/You came along to claim it.” Of course King’s “Natural Woman” does not summon the heavens with the same earth-shattering force as the Queen of Soul’s version, released in 1967. When King performed it live on tour with Taylor three years later, she would ask the audience to please imagine it as it once was—a demo for Aretha, and part of her life story. But the grasping of King’s “you make me”s and the fluttering of her “feel”s are charged with the force of a person attempting to turn herself inside out. In the voice of Aretha, “Natural Woman” is glory. In the voice of King, it is, like all of Tapestry, an act of pure conviction.

Though barely promoted by King herself, Tapestry spent 15 weeks as the No. 1 album in the U.S. upon its release, and stayed on the charts for five years. King won four Grammys for Tapestry in 1972, more than anyone had ever received at once, and it was the first time that the New York award ceremony was broadcast live on television. But King didn’t attend to collect the awards herself. She chose to remain in California with her newborn third child, Molly, instead.

It’s telling: There’s an unmistakable maternal energy to Tapestry. Throughout King’s career, she has recalled moments when her responsibilities merged, in which she’d have her baby in the playpen at the studio or be breastfeeding in between takes. Toni Stern has said that, while writing for Tapestry, King would be “playing the bass with her left hand and diapering a baby with her right.” King herself said that having kids kept her “grounded in reality,” which is audible in every loosely calibrated note of Tapestry. Her next artistic achievement was a collection of children’s music, 1975’s Really Rosie, in collaboration with author Maurice Sendak. A reworking of “Where You Lead”—rewritten, King has said, to sound less submissive—became the theme song to the mother-daughter sitcom “Gilmore Girls,” sung by King and her daughter Louise” – Pitchfork

Key Cut: It’s Too Late

T. Rex – Electric Warrior

Release Date: 24th September

Labels: Fly (U.K.)/Reprise (U.S.)

Producer: Tony Visconti

Standout Tracks: Cosmic Dancer/Jeepster/Life’s a Gas

Review:

“The album that essentially kick-started the U.K. glam rock craze, Electric Warrior completes T. Rex's transformation from hippie folk-rockers into flamboyant avatars of trashy rock & roll. There are a few vestiges of those early days remaining in the acoustic-driven ballads, but Electric Warrior spends most of its time in a swinging, hip-shaking groove powered by Marc Bolan's warm electric guitar. The music recalls not just the catchy simplicity of early rock & roll, but also the implicit sexuality -- except that here, Bolan gleefully hauls it to the surface, singing out loud what was once only communicated through the shimmying beat. He takes obvious delight in turning teenage bubblegum rock into campy sleaze, not to mention filling it with pseudo-psychedelic hippie poetry. In fact, Bolan sounds just as obsessed with the heavens as he does with sex, whether he's singing about spiritual mysticism or begging a flying saucer to take him away. It's all done with the same theatrical flair, but Tony Visconti's spacious, echoing production makes it surprisingly convincing. Still, the real reason Electric Warrior stands the test of time so well -- despite its intended disposability -- is that it revels so freely in its own absurdity and willful lack of substance. Not taking himself at all seriously, Bolan is free to pursue whatever silly wordplay, cosmic fantasies, or non sequitur imagery he feels like; his abandonment of any pretense to art becomes, ironically, a statement in itself. Bolan's lack of pomposity, back-to-basics songwriting, and elaborate theatrics went on to influence everything from hard rock to punk to new wave. But in the end, it's that sense of playfulness, combined with a raft of irresistible hooks, that keeps Electric Warrior such an infectious, invigorating listen today” – AllMusic

Key Cut: Get It On

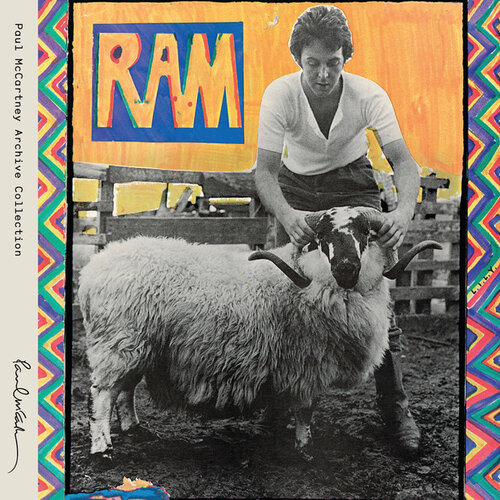

Paul and Linda McCartney – Ram

Release Date: 17th May

Label: Apple

Producers: Paul McCartney/Linda McCartney

Standout Tracks: Too Many People/Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey/Heart of the Country

Review:

“Despite reaching No. 1 in the UK and No. 2 in the US, Ram received harsh reviews, with Paul perceived as the bread-head who broke up the group. Yet decades on, as is so often the way, the music has triumphed, the antipathy set aside. Now, the cool thing to say is that the 1971 album – McCartney’s second post-Fabs, his last before Wings, and the only one co-billed with Linda – is one of his best.

Its stylistic grab-bag makes a highly entertaining spree, punctuated with bursts of true genius. There’s little coherence – it leaps restlessly from grandiose to silly, as is Macca’s way – but the best moments are breathtaking.

The UK single The Back Seat of My Car stalled, astonishingly, at number 39, but it’s a textbook example of why it’s impossible to sneer at this master craftsman for long. Romantic, surging, loaded with melodic twists and dynamic swoops which rip your heart out while smiling innocently, it’s a career pinnacle from a golden, competitive era.

Mr and Mrs McCartney sketched the songs while on a "get away from it all" holiday in the Mull of Kintyre, and then recorded in New York and L.A. with swiftly recruited musicians. Linda serves as backing vocalist (though she comes to the fore on Long Haired Lady).

Paul’s voice throughout shows uncanny range: although the whole vibe tries to say not-trying-too-hard, he proved a few points to Lennon. There are a couple of R&B plodders (Smile Away, Monkberry Moon Delight), but Heart of the Country is all rustic charm and the brilliant centre-piece (and US single) Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey is Abbey Road in microcosm.

Ripe for another re-evaluation, this reissue also offers rare/unreleased tracks, Paul’s orchestral version of the album, Thrillington, and that exquisite jewel, Another Day. Slaughtered at birth, Ram has lived on to fight” – BBC (Review of the Deluxe Version)

Key Cut: The Back Seat of My Car

John Lennon - Imagine

Release Date: 9th September

Label: Apple

Producers: John Lennon/Yoko Ono/Phil Spector

Standout Tracks: Imagine/Gimme Some Truth/Oh My Love

Review:

“A personal statement in the form of an honest and heartfelt apology and asking for forgiveness, “Jealous Guy” is a pleasant song. Spector’s presence is obvious, with the trademark strings building behind the fine ballad. Spector-ization of this album is a double edged sword – the simple, honest themes are probably best in their stripped down version, but Spector’s production does add a bit of richness and commercial appeal

Despite the strength of “Imagine” and “Jealous Guy,” The first side of the album is bogged down with much filler and is ultimately much weaker and less interesting than side two, where the action is. From the simple love song, “Oh My Love” to the deep, introspective “How?”, which includes perhaps the best lyric on the album-

“How can I go forward when I don’t know which way I’m facing?”

The second side also includes a very personal dig at Lennon’s former bandmate and songwriting partner. Earlier in 1971, Paul McCartney had released his second solo album Ram, which contained the opening song “Too Many People” that had some harsh lyrics directed at John and his wife, Yoko Ono. “John had been doing a lot of preaching”, McCartney admitted in 1984. “I wrote, ‘Too many people preaching practices,’ that was a little dig at John and Yoko”. “How Do You Sleep?” was a direct response, with even less veiled criticism that directly took on McCartney with clear references and double-entendres.

“Gimme Some Truth” is the best song on this album. It is a rant expressing John’s frustration with the general bullshit of life and society. It features scathing lyrics delivered in a syncopated rhythm against a background heavy with bass and drums –

“I’m sick to death of seeing things from tight-lipped, condescending, mama’s little chauvinists All I want is the truth Just gimme some truth now I’ve had enough of watching scenes of schizophrenic, ego-centric, paranoiac, prima-donnas”

It is a precise statement about politicians lying and propagandizing – cut the crap and just tell the truth.

Although the album features Beatles band mate George Harrison as lead guitarist, he does not shine too brightly at any one moment. Pianist Nicky Hopkins, however, provides some great virtuoso and memorable playing, especially on “Crippled Inside”, “Jealous Guy”, and the upbeat pop song, “Oh Yoko!”. Alan White takes over for Ringo on drums and there are many guest musicians, including several members of the band Badfinger.

On Imagine, John Lennon slides from themes of love, life, political idealism, to raw emotion. Honesty is an ongoing theme in his lyrics, especially after he descends from the polyanic vision of the theme song. It settles on the more realistic theme of life is not perfect, but if one lives honestly, loves fully and rises above the conflicts, it’s pretty close” – Classic Rock

Key Cut: Jealous Guy

Sly & The Family Stone - There's a Riot Goin' On

Release Date: 1st November

Label: Epic

Producer: Sly Stone

Standout Tracks: Just Like a Baby/Runnin' Away/Thank You for Talkin' to Me Africa

Review:

“It's easy to write off There's a Riot Goin' On as one of two things -- Sly Stone's disgusted social commentary or the beginning of his slow descent into addiction. It's both of these things, of course, but pigeonholing it as either winds up dismissing the album as a whole, since it is so bloody hard to categorize. What's certain is that Riot is unlike any of Sly & the Family Stone's other albums, stripped of the effervescence that flowed through even such politically aware records as Stand! This is idealism soured, as hope is slowly replaced by cynicism, joy by skepticism, enthusiasm by weariness, sex by pornography, thrills by narcotics. Joy isn't entirely gone -- it creeps through the cracks every once and awhile and, more disturbing, Sly revels in his stoned decadence. What makes Riot so remarkable is that it's hard not to get drawn in with him, as you're seduced by the narcotic grooves, seductive vocals slurs, leering electric pianos, and crawling guitars. As the themes surface, it's hard not to nod in agreement, but it's a junkie nod, induced by the comforting coma of the music. And damn if this music isn't funk at its deepest and most impenetrable -- this is dense music, nearly impenetrable, but not from its deep grooves, but its utter weariness. Sly's songwriting remains remarkably sharp, but only when he wants to write -- the foreboding opener "Luv N' Haight," the scarily resigned "Family Affair," the cracked cynical blues "Time," and "(You Caught Me) Smilin'." Ultimately, the music is the message, and while it's dark music, it's not alienating -- it's seductive despair, and that's the scariest thing about it” – AllMusic

Key Cut: Family Affair