FEATURE:

Across the Lines

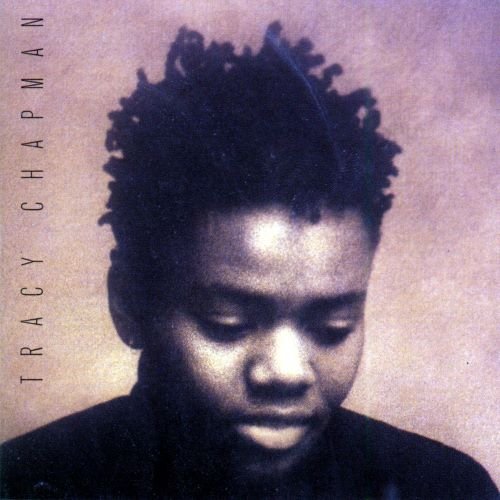

Tracy Chapman at Thirty-Five

_________

A tremendous and timeless eponymous album…

PHOTO CREDIT: Dave Hogan/Getty Images (via Rolling Stone)

Tracy Chapman is thirty-five on 5th April. The Ohio-born artist released a work of profound depth and genius with her debut. Recorded at the Powertrax studio in Hollywood, I have been playing it this week and discovering new layers and lines. The story of how she came to record her debut and get signed is interesting. In 1987, Chapman was discovered by fellow Tufts University student Brian Koppelman. Koppelman offered to show her music to his father. He owned a successful publishing company. Tracy Chapman was sceptical as to the validity of the offer, so it was not persuaded Eventually, Koepplman found a recording of her singing Talkin' 'bout a Revolution, which he then promoted to radio stations, and she was eventually signed to Elektra Records. It was hard getting a producer for the album, as many were not fond or sure of her musical direction. Maybe not used to an artist like this. David Kershenbaum produced Tracy Chapman, and he was keen to record an acoustic music album. Recorded in eight weeks, Chapman’s amazing debut deals with political and social issues. So many of the themes and messages are relevant and powerful to this day. I will come to reviews of Tracy Chapman soon. Before that, there are features that give us some background to one of the great debut albums. Dig! wrote about the album last year. They highlighted the hugely successful single, Fast Car, and the fact Tracy Chapman was number one in the U.S. and U.K. It was a massive success at the time, and it is frequently seen as one of the greatest and most influential albums ever:

“Tracy Chapman was, in some ways, a very traditional troubadour. She was a young, socially-conscious woman and a fixture in coffeehouses in the town where she was studying (Danbury, Connecticut). Her debut album was an outgrowth from this period of her life – all of the songs on the album, with the exception of Fast Car, came from an early demo tape. She was “discovered” by another student, who introduced her to his father, the head of a publishing company. A deal with Elektra Records followed.

But that’s where the well-trodden routes stop. What Tracy Chapman did, on her self-titled debut album, was to fuse two distinct approaches, and her genius was to go beyond the niche. Instead, she looked outwards, embracing accessibility, and in doing so her music gave voice to millions, many of them marginalised because of race, gender, class or sexuality.

The first tradition that Chapman is from is perhaps the most obvious: protest music, equal parts feminist protest music and Black radicalism. Before she was famous, Chapman picked words from the African-American poet and spoken-word artist Nikki Giovanni to accompany her entry in her high-school yearbook. “There is always something to do,” Chapman quoted. “There are hungry people to feed, naked people to clothe, sick people to comfort and make well.” Giovanni’s work, alongside that of other uncompromising folk artists, are steel threads through Chapman’s debut album. “They wrote their own songs, they played them, they performed by themselves,” Chapman said in 1988, speaking of female folk singers in an interview for Rolling Stone. “There you have a picture of a very independent person.” Chapman’s debt to 70s women-only festivals, female-led record labels and wider feminist activism is there in her subject matter (including domestic abuse, sexual assault and women’s lack of opportunities), alongside her fierce independence.

The second tradition to birth Chapman’s debut album is found in pop and rock music’s working-class intellectuals: everyone from Dolly Parton to Mark E Smith, Johnny Cash to John Lydon. Like those artists, Chapman’s childhood poverty helped her develop a clarity about the societal systems that sustained despair, ignorance and prejudice. The community of Cleveland, Ohio, where Chapman grew up, was not only poor; it was also segregated and racially tense. “The city had been forced to integrate the schools,” said Chapman in 2008, looking back at her childhood. “They were bussing Black children into white neighbourhoods, and white children into Black neighbourhoods, and people were upset about it so there were race riots.

The third track on Tracy Chapman’s self-titled debut album, Across The Lines, deals with this directly: white and Black children, transported to school, on the frontline of North America’s angry racism. Chapman saw clearly how aggression and resentment was maintained as poor people were forced to fight each other over scraps while being sold the dream of “mountains o’ things”, to quote another of the album’s songs. Chapman maintains compassion for even those who deal out violence, understanding that structural forces in society are beyond an individual’s control. Behind The Wall, for example, a track about overhearing domestic abuse, is as critical of the inert police response as it is of the man doling out the attacks”.

Opening with there of the finest run of three tracks you can imagine with Talkin’ Bout a Revolution, Fast Car, and Across the Lines, Tracy Chapman gets under the skim right away. It is beautifully balanced so that its strongest songs are distributed equally throughout, so that you get this consistency and satisfying listening experience. In fact, the final track on the album, For You, is a perfect way to end – and a song that few people discuss when they talk about Tracy Chapman’s debut album. Albumism spotlight Tracy Chpaman in 2018 for the thirtieth anniversary. We discover more about Chapman as an artist and why she brings such depth, passion, weight and wonder on her debut:

“The way Chapman’s voice creaks and breaks with nearly every syllable of the verse makes her telling of life heart-wrenching without overplaying the sentiment. So when she arrives at the chorus and sings, “I had a feeling that I belonged / I had a feeling I could be someone, be someone” with a sense of power and conviction, you’ve already signed up for the journey. And whilst she offers no clear-cut answer and leaves the narrative of “Fast Car” open-ended, that’s part of its appeal. There’s realness in the uncertainty of life at play here, the push and pull of desire and reality that can leave the song feeling at once optimistic and dour.

If “Fast Car” was her take on the minutiae of our daily lives, album opener “Talkin’ ‘Bout a Revolution” painted with broader, more socially conscious strokes. And with a title like that, how could it not?

Hitting with brewing defiance “Talkin’ ‘Bout a Revolution” threatens the privilege of the status quo as she sings, “Poor people gonna rise up and take their share / Poor people gonna rise up and take what’s theirs” and later “Finally, the tables are starting to turn.” It’s fitting that she sings “Don’t you know / They’re talkin’ ‘bout a revolution / and it sounds like a whisper” with a quiet confidence that a popular uprising is looming in the unvoiced frustrations of the everyday person. This is a folk master class in narrative, arrangement and production and remains an album highlight.

Elsewhere on the album, Chapman’s social-consciousness hones in on the racial divide in America with “Across the Lines,” as she recounts a tale of racial attacks and the ensuing fallout and mourns, “On the back streets of America / They kill the dream of America.”

Similarly with the soulful a capella of “Behind the Wall,” Chapman laments the cycle of domestic violence and the inaction of the police to “interfere with domestic affairs between a man and his wife.” It’s sobering stuff, made even more powerful by having only Chapman’s vocals carry the song as the sole voice calling out in the dark, shedding light on a broken system and the helplessness of victims.

Chapman’s observations aren’t just focused on the world outside her door and some of the album’s most touching moments come through the intimate reflections on personal relationships. Songs like the beautiful “Baby Can I Hold You,” which touches on the simple things needed to sustain a relationship and “For My Lover,” which reflects on the themes of forbidden love through the guise of an interracial and/or same sex relationship — both equally vilified in the America of its era — carry an honest sweetness to them that makes them immediately intriguing”.

I am going to come to a couple of reviews to round things off. On 5th April, we will mark the thirty-fifth anniversary of the stunning Tracy Chapman. Her latest studio album, the underrated Our Bright Future, was released in 2008. I hope that we get more music from this incredible artist. Pitchfork gave Tracy Chapman 9.4 in 2019 when they sat down and reviewed it:

“It was in a black neighborhood in this roiling cityscape that her mother Hazel raised Chapman and her older sister by herself. Together, the family sang along to Top 40 radio and Hazel’s collection of jazz, gospel, and soul records, including Mahalia Jackson, Curtis Mayfield, and Sly Stone. Meanwhile, television exposed a young Chapman to the country music stylings of Buck Owens and Minnie Pearl on the show “Hee Haw.” She was already playing ukulele and started writing songs by age 8, took up guitar at 11, and at 14 wrote her first song looking at the troubles in her city. She called it “Cleveland 78.”

Though Chapman left Cleveland while she was still a teenager, having earned a scholarship to a private, Episcopal boarding school in Connecticut, her debut offers a working-class, undeniably black perspective. There’s “Across the Lines,” in which Chapman describes, over halting guitar strums and a twinkling dulcimer, a segregated city breaking out in a fatal riot. Sparked by news that a white man assaulted a black girl, the incident is ultimately blamed on the victim. “Choose sides/Run for your life/Tonight the riots begin/On the back streets of America/They kill the dream of America,” Chapman sings in a stoic murmur. There’s “Mountain O’ Things” where she voices the dubious dreams sold to the American poor. “I won’t die lonely,” she sings against a soft marimba and hand drum beats. “I’ll have it all prearranged/A grave that’s deep and wide enough/For me and all my mountains o’ things.”

Yet, for all the violence and hopelessness Chapman captures in her lyrics, there’s an equal measure of radical and at times naive conviction that a more just world is on its way. “Why?” asks basic questions about widespread injustices—“Why is a woman still not safe/When she’s in her home”—before answering with an insistent assurance that “somebody’s gonna have to answer” for the destruction modern society has wrought. “Talkin’ ‘Bout a Revolution,” the opening song, is arguably the clearest view into Chapman’s political ethos. It’s a simple folk-pop anthem with a fervent, bright-eyed assurance that “Poor people gonna rise up/And get their share.” These brazen statements of faith in a better future emerge as encouragements for the downtrodden to continue on. Only someone who has seen society’s murky underbelly can convince you of its redeemability. She wrote the song when she was 16.

The dreams of social justice running through the entire album offset Tracy Chapman from its top-selling contemporaries. But with the eponymous words of “For You” resonating into the final seconds, love emerges as the underlying motivation for survival. Love is what all the figures she gives voice to ultimately want. And thanks to Chapman’s careful wording—the lover of the “checkout girl” from “Fast Car” is never gendered, while the only gendered part of the downbeat and mysteriously desperate “For My Lover” comes with the line “deep in this love/No man can shake”—it’s a body of work that one can easily read centered on queer desire. Chapman was notoriously private about her own sexuality and romantic life, even as she created love songs that welcomed all listeners to share in its subjectivity.

After its release, critics praised the album for its overtly political focus, hailing it as popular music’s return to authentic artistry. But Tracy Chapman didn’t change the course of a Top 40 ecosystem in tune with the era’s glorification of wealth and greed. Rather, the album was produced in isolation from popular music, and in defiance of it. She wasn’t a herald of change within the industry so much as she was an example of the innovation to be found outside of it. In pop music at the time, there was no archetype with which to classify the kind of artist Chapman was. And so, as she shrunk away from the spotlight, so did the gritty environment that contextualized her and her work.

Though the album showcased a descendant of white artists like Baez and Dylan, it also showed one who drew from the spiritual folks stylings of Odetta and the influence of blues singers like Bessie Smith. Nevertheless, once she rose to fame, critics debated the relative blackness of her music, her audience, and by extension herself. In 1989, Public Enemy’s Chuck D summed up a sentiment some critics touched on regarding the perceived whiteness of her audience frankly for Rolling Stone: “Black people cannot feel Tracy Chapman, if they got beat over the head with it 35,000 times.” The lack of nuance leveled at her music and identity highlighted just how far outside of the mainstream her artistry was rooted, and just how little mainstream outlets understood about black artists and audiences, even as Tracy Chapman held steady on the Billboard charts”.

I will finish off with a review from AllMusic. They discuss the political context of the album, and why it was so stirring and relevant in 1988. As I said, I think that it is very potent and relevant today. What Chapman discusses and sings about can apply to society and politics now:

“Arriving with little fanfare in the spring of 1988, Tracy Chapman's eponymous debut album became one of the key records of the Bush era, providing a touchstone for the entire PC movement while reviving the singer/songwriter tradition. And Tracy Chapman is firmly within the classic singer/songwriter tradition, sounding for all the world as if it was recorded in the early '70s -- that is, if all you paid attention to were the sonics, since Chapman's songs are clearly a result of the Reagan revolution. Even the love songs and laments are underscored by a realized vision of trickle-down modern life -- listen to the lyrical details of "Fast Car" for proof. Chapman's impassioned liberal activism and emotional resonance enlivens her music, breathing life into her songs even when the production is a little bit too clean. Still, the juxtaposition of contemporary themes and classic production precisely is what makes the album distinctive -- it brings the traditions into the present. At the time, it revitalized traditional folk ideals of social activism and the like, kick starting the PC revolution in the process, but if those were its only merits, Tracy Chapman would sound dated. The record continues to sound fresh because Chapman's writing is so keenly observed and her strong, gutsy singing makes each song sound intimate and immediate”.

A startling and enormously successful album that turns thirty-five on 5th April, Tracy Chapman should be heard by everyone! Credited with reviving the singer-songwriter tradition, and defining the Bush era, there was no real big explosion or hype when Tracy Chapman came out in 1988. It was praised for combining modern themes and ideas with a classic production style. You get something vintage and heritage with urgency and fresh perspectives. That is why the remarkable Tracy Chapman will…

NEVER lose its power and brilliance.