FEATURE:

Heading Through the Morning Fog

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush in 1980

Ranking Kate Bush’s Penultimate and Final Track Combinations

_________

IN terms of Kate Bush’s…

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush shot for Q magazine in 1993/PHOTO CREDIT: John Stoddart

albums and dissecting them, I have produced a few features around them. In terms of track order. I have ranked her best album openers. I have also looked at the final tracks. One feature ranked the best first side closers and second side openers. That important combination. In terms of combinations, I have not yet looked at the one-two of the penultimate and closing track. I don’t think there is any other pairing I can look at, so this might be one of the last types of features like this I’ll put out. It is important to leave the listener on a high. Closing an album in style. Kate Bush is brilliant when it comes to sequencing. However, as mentioned in similar features, some albums are better sequenced than overs. Making sure the opening couple of tracks are brilliant. A strong middle and a wonderful final couple of songs. I am focusing on that latter partnership. Ten studio albums to rank. Which one has the best final two tracks. There is tough competition! I am not only taking into consideration the quality of the tracks but how they fit together and the impact they make. Many might disagree with my rankings. However, there is my opinion of which Kate Bush albums have the best…

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush watching the rushes during filming of The Line, the Cross and the Curve in 1993/PHOTO CREDIT: Guido Harari

PENULTIMATE and final tracks.

_______________

TEN: The Red Shoes (1993): Why Should I Love You?/You’re the One

“Bush was in a strange place when she met the Purple One. Her close friend and guitarist Alan Murphy had just died of AIDS-related pneumonia, she was going through the motions of a relationship breakdown, and was teetering on the cusp of a break from music, which, when it came, would actually last for 12 years. Prince, on the other hand, was going through one of his many spiritual rebirths. He had just emerged from the murky shadows of The Black Album, a creation he withdrew a week after release because he was convinced it was an evil, omnipotent force. He vaulted out of that hole, into a period of making music that was upbeat, pop-tinged and pumped up. In essence, the two artists’ headspaces could not really have been in more opposite places; Prince, artistically baptised and ready to change the world, and Kate Bush, surrounded by a fog of melancholia and disarray.

Prince had been a huge Kate Bush admirer for years. In emails exchanged in 1995 between Prince’s then-engineer Michael Koppelman and Bush’s then-engineer Del Palmer, Koppelman says that Prince described her as his “favourite woman”. But despite both artists being active since the 70s, it wasn’t until 1990 that they actually met in real life. Bush attended a Prince gig at Wembley during his monumental Nude Tour, asked to meet him backstage, and the rest is God-like genius collaboration history.

Perhaps it was the sheer distance between their headspaces at the time that led to what happened. Bush asked Prince to contribute a few background vocals to a song called “Why Should I Love You”, which she had just recorded in full at Abbey Road Studios. But when Prince received the track, he ignored the intructions and dismantled the entire thing like a crazed mechanic taking apart old cars on his backyard. He wanted to inject himself into the very heart of it, weaving his sound amongst her sound, giving it a new soul entirely. As Koppelman explains, “We essentially created a new song on a new piece of tape and then flew all of Kate’s tracks back on top of it… Prince stacked a bunch of keys, guitars, bass, etc, on it, and then went to sing background vocals.”

Despite being the lovechild of two of humanity’s greatest music minds, the resulting track is not often mentioned on your average BBC3 pop retrospective presented by Lauren Laverne. It’s startlingly brilliant, with sometimes bizarre, musical depths. It begins as a typical Kate Bush creation; her stratospheric vocals rising across a strange organ melody and tumbling drums. But then, about a minute through, it mutates like an unstable element being dropped into boiling water. Prince invades in a huge wave of gospel sound, the pair singing in unison: “Of all of people in the world, why should I love you?” By the time it reaches the 2-minute mark, it has been completely permeated with that Paisley Park flavour; smatters of electric guitar and rich walls of vocals spilling over its borders. The purple sound arrives like a tsunami, seemingly too vivid to suppress” – VICE

“It’s alright I’ll come ’round when you’re not in

And I’ll pick up all my things

Everything I have I bought with you

But that’s alright too

It’s just everything I do

We did together

And there’s a little piece of you

In whatever

I’ve got everything I need

I’ve got petrol in the car

I’ve got some money with me

There’s just one problem

You’re the only one I want

You’re the only one I want

You’re the only one I want

You’re the only one I want

It’s alright I know where I’m going

I’m going to stay with my friend

Mmm, yes, he is very good looking

The only trouble is

He’s not you

He can’t do what you do

He can’t make me laugh and cry

At the same time

Let’s change things

Let’s danger it up

We’re crazy enough

I just can’t take it

You’re the only one I want

You’re the only one I want

You’re the only one I want

You’re the only one I want

I know where I’m going

But I don’t want to leave

I just have one problem

We’re best friends, yeah?

We tied ourselves in knots

Doing cartwheels ‘cross the floor

Just forget it alright

Sugar?…

Honey?…

Sugar?…

Credits

Drums: Stuart Elliott

Bass: John Giblin

Guitar: Jeff Beck

Hammond: Gary Brooker

Vocals: Trio Bulgarka

Fender Rhodes, keyboards: Kate” – Kate Bush Encyclopedia

NINE: Director’s Cut (2011): And So Is Love/Rubberband Girl

“Versions

There are two versions of ‘And So Is Love’: the album version from 1993, and the version from Bush’s album Director’s Cut in 2011, on which the key lyric ‘But now we see that life is sad’ is changed to ‘But now we see that life is sweet’.

Music video

The music video for ‘And So Is Love’ was also used in the movie The Line, The Cross and The Curve and features Kate singing the song in a dark room lit only by a candle.

Performances

After the release of the single, it climbed to number 26 in the UK singles chart. The chart entry marked Bush’s first appearance on the chart show Top Of The Pops in nine years. It was a straightforward performance with Kate lipsynching the song in front of the studio audience with two female backing singers by her side” - Kate Bush Encyclopedia

“When Kate returned in 1993, reviews of the lead single of The Red Shoes were positive but not ecstatic.

This is Bush at her most direct… rhythmic, almost raunchy workout with the occasional outburst of rock guitar, strange lyrics – and a wired vocal impression of said office accessory being stretched. It is also a very commercial rejoinder.

Alan Jones, Music Week, 28 August 1993

Perhaps a little too up tempo for my tastes – I prefer my Bush all dreamy and mysterious. A minus the drums… but it still has enough kookiness to draw me under. And she’s still the only artist for whom the word “kooky” isn’t an insult.

Everett True, Melody Maker, 11 September 1993

“I thought the original ‘Rubberband’ was… Well, it’s a fun track. I was quite happy with the original, but I just wanted to do something really different. It is my least favourite track. I had considered taking it off to be honest. Because it didn’t feel quite as interesting as the other tracks. But I thought, at the same time, it was just a bit of fun and it felt like a good thing to go out with. It’s just a silly pop song really, I loved Danny Thompson’s bass on that, and of course Danny (McIntosh)’s guitar.

Mojo (UK), 2011 – Kate Bush Encyclopedia

EIGHT: The Sensual World (1989): Rocket’s Tail/This Woman’s Work

“Rock music was really in some state of transition at the time, even though Kate seems always to have functioned on some outer edge wherein the rules did not apply. So many tracks on this album stand out, and it feels like the very personification of Autumn to me.

“Never Be Mine” is filled with the bittersweet yearning of “they’re setting fire to the corn fields as you’re taking me home” which resolves with “the smell of burning fields will now mean you and here/and this is where I want to be, this is what I need/but I know that this will never be mine.” Beautiful and sad. Fall is the time when we put the past to bed and settle in for winter’s nap, or at least a nice cup of tea by the fire. This album is glorious, and is heard to best effect this time of year.

My favorite track from the album is “Rocket’s Tail” for many reasons, but it sets itself indubitably in a particular time by announcing it happened one November night from the very first line. The track opens with the sinuous harmonies of Trio Bulgarka. The ethereal beauty of Kate’s voice threads nicely through the confounding tones of the Bulgarian voices, to magnificent effect.

That November night, looking up into the sky

You said hey wish that was me up there

It's the biggest rocket I could find

And it's holding the night in its arms

If for only a moment

I can't see the look in its eyes

But I'm sure it must be laughing

I once heard that Rocket was Kate’s cat, but it doesn’t really matter, because it’s such a pretty story. I mean, it MUST be true, right? Anyone who’s seen cat zoomies can attest that they’d shoot across the sky like a meteor if they could, and who better than a cat can demonstrate a tail on fire?

But it seemed to me the saddest thing I'd ever seen

And I thought you were crazy wishing such a thing

I saw only a stick on fire

Alone on its journey

Home to the quickening ground

With no one there to catch it

The poignance of this set of lines blew me away, that where the intrepid cat saw excitement and adventure and the sheer thrill of adrenaline-inducing hijinks, the speaker would see isolation in the vast chill of space.

Oh, but then she joins in the fun:

I put on my pointed hat

And my black and silver suit

And I check my gunpowder pack

And I strap the stick on my back

And dressed as a rocket on Waterloo Bridge

Nobody seemed to see me

Nutty lady on London’s Waterloo Bridge making like a bottle rocket? I’m down with this. Can I play, too?

Then with the fuse in my hand

And now shooting into the night

A fretless bass has wound through the proceedings at this point. He is not credited on this track, but I feel this can only be Mick Karn, who played on another track on the the album whence this track originates. Superb. Mick Karn was pure magic. Gone far too soon. Just like him to blend into the shadows and let his music coil through the dance.

And still as a rocket

I land in the river

Was it me said you were crazy?

And then we get the full glory that can only be the guitar of David Gilmour. How did this thing go from glorious to impossibly wonderful? Yes. Just like this.

I put on my cloudiest suit

Size five lightning boots too

'Cause I am a rocket

On fire

Look at me go with my tail on fire

Tail on fire

On fire

Between the otherworldly vocals and the stratospheric squealings of David Gilmour's guitar, this track is one for the sci-fi ages. We’re imagining ourselves elsewhere. We’re dreaming and we’re reaching. If we aspire to take the night in our arms, who is there to stop us?” – Raconteur Press

“John Hughes, the American film director, had just made this film called ‘She’s Having A Baby’, and he had a scene in the film that he wanted a song to go with. And the film’s very light: it’s a lovely comedy. His films are very human, and it’s just about this young guy – falls in love with a girl, marries her. He’s still very much a kid. She gets pregnant, and it’s all still very light and child-like until she’s just about to have the baby and the nurse comes up to him and says it’s a in a breech position and they don’t know what the situation will be. So, while she’s in the operating room, he has so sit and wait in the waiting room and it’s a very powerful piece of film where he’s just sitting, thinking; and this is actually the moment in the film where he has to grow up. He has no choice. There he is, he’s not a kid any more; you can see he’s in a very grown-up situation. And he starts, in his head, going back to the times they were together. There are clips of film of them laughing together and doing up their flat and all this kind of thing. And it was such a powerful visual: it’s one of the quickest songs I’ve ever written. It was so easy to write. We had the piece of footage on video, so we plugged it up so that I could actually watch the monitor while I was sitting at the piano and I just wrote the song to these visuals. It was almost a matter of telling the story, and it was a lovely thing to do: I really enjoyed doing it - Roger Scott Interview, BBC Radio 1 (UK), 14 October 1989

That’s the sequence I had to write the song about, and it’s really very moving, him in the waiting room, having flashbacks of his wife and him going for walks, decorating… It’s exploring his sadness and guilt: suddenly it’s the point where he has to grow up. He’d been such a wally up to this point - Len Brown, ‘In The Realm Of The Senses’. NME (UK), 7 October 1989” – Kate Bush Encyclopedia

SEVEN: The Kick Inside (1978): Room for the Life/The Kick Inside

“Room for the Life” is that rare thing in Kate Bush’s early discography: a song presenting a dialogue between two women. You’d think this would be particularly refreshing, but there’s something odd about “Room for the Life”: nobody ever talks about it. That’s not to say there’s not a single person in the world who doesn’t enjoy the song — it’d be astonishing if in the four decades since The Kick Inside was released nobody had liked “Room for the Life.” But the song is hindered by the fact it’s not any good. It’s easily the worst track on The Kick Inside: ham-fisted, embarrassing, and just plain forgettable.

Musically, “Room for the Life” is a trainwreck. Its verse blends into the rest of The Kick Inside, offering little in the way of standing out, and the chorus does little to liven up the song, with its tepid use of beer bottles as an instrument only succeeding in making the track sound flaccid. The worst comes at the end of the chorus, with Bush chiming “mama woman aha!” obnoxiously. This culminates in the song’s outro, with Bush imitating… what is she doing here exactly? Percussionist Morris Pert’s boo-bams (a kind of bongos) bring a light world music flavor to it, amplified by Bush’s grating “OO-AH”s. It’s one of the most tasteless moments on an otherwise sophisticated record, and releasing a track like this instead of “Frightened Eyes” is a downright baffling move on Bush’s part.

In addition to its musical tastelessness, “Room for the Life” is out of touch. Bush has identified herself with male artists, admitting that a lack of interesting female songwriters was the reason (she cites Joni Mitchell, Billie Holliday, and Joan Armatrading as exceptions). When she writes about two female characters in “Room,” things fall apart (this isn’t always the case — my favorite Kate Bush song is a woman-centered dialogue, as we’ll see). The song is addressed from one woman to another, telling of the magical power of women, expressed as a singularity with the oddly agrammatical phrase “because we’re woman.” It’s an oddly naïve little song, and one with strange conclusions on how to be a woman. “Lost in your men and the games you play/trying to prove that you’re better woman,” Bush chides her friend. How dare she try to get ahead of men. The audacity of it” – Dreams of Orgonon

“The song The Kick Inside, the title track, was inspired by a traditional folk song and it was an area that I wanted to explore because it’s one that is really untouched and that is one of incest. There are so many songs about love, but they are always on such an obvious level. This song is about a brother and a sister who are in love, and the sister becomes pregnant by her brother. And because it is so taboo and unheard of, she kills herself in order to preserve her brother’s name in the family. The actual song is in fact the suicide note. The sister is saying ‘I’m doing it for you’ and ‘Don’t worry, I’ll come back to you someday.’ - Self Portrait, 1978

That’s inspired by an old traditional song called ‘Lucy Wan.’ It’s about a young girl and her brother who fall desperately in love. It’s an incredibly taboo thing. She becomes pregnant by her brother and it’s completely against all morals. She doesn’t want him to be hurt, she doesn’t want her family to be ashamed or disgusted, so she kills herself. The song is a suicide note. She says to her brother, ‘Don’t worry. I’m doing it for you.’- Jon Young, Kate Bush gets her kicks. Trouser Press, July 1978” – Kate Bush Encyclopedia

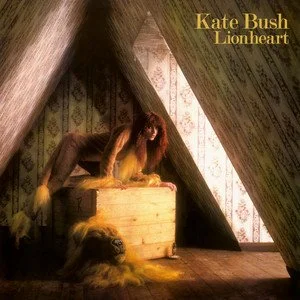

SIX: Lionheart (1978): Coffee Homeground/Hammer Horror

“[‘Coffee Homeground’] was in fact inspired directly from a cab driver that I met who was in fact a bit nutty. And it’s just a song about someone who thinks they’re being poisoned by another person, they think that there’s Belladonna in their tea and that whenever they offer them something to eat, it’s got poisen in it. And it’s just a humorous aspect of paranoia really and we sort of done it in a Brechtian style, the old sort of German [vibe] to try and bring across the humour side of it - Lionheart Promo Cassette, EMI Canada, 1978” – Kate Bush Encyclopedia

“Resultingly, Bush’s engagement with Epic Theater is a purely audible one. “Homeground” owes more to Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya than it does to Brecht, as it’s their sound Bush pillages. Bush’s trill becomes a half-spoken warble as she strives to sound like Lenya for a track. It’s not a bad impression — sure, it sounds nothing like Lenya’s voice, but Bush doesn’t do the worst job of imitating her speech patterns. Musically, the strongest resemblance to Brecht and Weill’s work here is the morbid subject matter applied to carnivalesque scoring. The melody contains huge leaps and never sounds quite the same, as the intro and bridge repeat essentially the same phrase in a different key every time they appear. There are little discordant details such as the use of the non existent #VII chord of B flat (A), which doesn’t appear in B flat major or B flat minor. The pre-chorus will make a play at being in A before transforming into some mode of B (possibly mixolydian, or anything with a flattened seventh). Even if “Homeground” lacks conceptual clarity, it’s far from banal.

The decrepit house of “Homeground” is as much a stage for the song itself as it is for Bush. In a period where she’s torn between the obligations of touring and her desire to give her songs the time they need, “Coffee Homeground” is the sort of song Kate Bush is bound to produce. Her shortcomings and her ambition clash violently, and the result is as fascinating and vexed as anything she’s ever made. This has been a challenging period for Bush, and as we’ll see in the next two weeks, it’s about to climax” – Dreams of Orgonon

“The song is not about, as many think, Hammer Horror films. It is about an actor and his friend. His friend is playing the lead in a production ofThe Hunchback of Notre Dame,a part he’s been reading all his life, waiting for the chance to play it. He’s finally got the big break he’s always wanted, and he is the star. After many rehearsals he dies accidentally, and the friend is asked to take the role over, which, because his own career is at stake, he does. The dead man comes back to haunt him because he doesn’t want him to have the part, believing he’s taken away the only chance he ever wanted in life. And the actor is saying, “Leave me alone, because it wasn’t my fault – I have to take this part, but I’m wondering if it’s the right thing to do because the ghost is not going to leave me alone and is really freaking me out. Every time I look round a corner he’s there, he never disappears.”

The song was inspired by seeing James Cagney playing the part of Lon Chaney playing the hunchback – he was an actor in an actor in an actor, rather like Chinese boxes, and that’s what I was trying to create - Kate Bush Club Newsletter, November 1979” – Kate Bush Encyclopedia

FIVE: Aerial (2005): Nocturn/Aerial

“For instance, the lyrics of Nocturn is a beautiful description of awakening to – or at least intuiting – Big Mind. God as all and ourselves as That.

Interpreting can only detract from it, but here is a go at it…

Nocturn

On this Midsummer night

Everyone is sleeping

We go driving into the moonlight

Could be in a dream

Our clothes are on the beach

These prints of our feet

Lead right up to the sea

No one, no one is here

No one, no one is here

We stand in the Atlantic

We become panoramic

No one is here – this probably means that there were no others there, but can also be seen as the realization that there is no “I” – there is no one here. I am gone, and there is only God. We become panoramic – the world world is within us.

We tire of the city

We tire of it all

We long for just that something more

Yes, a longing for discovering our true nature. As that which is, with no “I” anywhere. As consciousness and all its manifestations.

Could be in a dream

Our clothes are on the beach

The prints of our feet

Lead right up to the sea

No one, no one is here

No one, no one is here

We stand in the Atlantic

We become panoramic

The stars are caught in our hair

The stars are on our fingers

A veil of diamond dust

Just reach up and touch it

The sky’s above our heads

The sea’s around our legs

In milky, silky water

We swim further and further

The universe happens within and as us, and the stars are caught in our hair and the stars are on our fingers. The can be seen as a beautiful expression of the play of the absolute and relative, as ourselves as Big Mind and a human self.

We dive down… We dive down

A diamond night, a diamond sea

and a diamond sky…

When the realization of no “I” pops, there is indeed a diamond quality to it all. It is brilliantly clear, stainless.

We dive deeper and deeper

we dive deeper and deeper

Could be we are here

Could be in a dream

It came up on the horizon

Rising and rising

In a sea of honey, a sky of honey

A sea of honey, a sky of honey

And here is the bliss that comes with an awakening. The sea and sky of honey that comes with the release from the previous contractions.

The chorus:

Look at the light, all the time it’s a changing

Look at the light, climbing up the aerial

Bright, white coming alive jumping off of the aerial

All the time it’s a changing, like now…

All the time it’s a changing, like then again…

All the time it’s a changing

And all the dreamers are waking

Finding ourselves as the ground, as that from and as the world of form arises, as emptiness dancing, we see clearly how the world of form is always changing. And there is no need to hold onto anything.

This is the dreamers waking. And each one of us is the dreamer waiting to awaken” – Absentofi

“The dawn has come

And the wine will run

And the song must be sung

And the flowers are melting

In the sun

I feel I want to be up on the roof

I feel I gotta get up on the roof

Up, up on the roof

Up, up on the roof

Oh the dawn has come

And the song must be sung

And the flowers are melting

What kind of language is this?

What kind of language is this?

I can’t hear a word you’re saying

Tell me what are you singing

In the sun

All of the birds are laughing

All of the birds are laughing

Come on let’s all join in

Come on let’s all join in

I want to be up on the roof

I’ve gotta be up on the roof

Up, up high on the roof

Up, up on the roof

In the sun

Credits

Drums: Steve Sanger

Bass: Del Palmer

Guitars: Dan McIntosh

Keyboards: Kate

Percussion: Bosco D’Oliveira” – Kate Bush Encyclopedia

FOUR: 50 Words for Snow (2011): 50 Words for Snow/Among Angels

“Years ago I think I must have heard this idea that there were 50 words for snow in this, ah, Eskimo Land! And I just thought it was such a great idea to have so many words about one thing. It is a myth – although, as you say it may hold true in a different language – but it was just a play on the idea, that if they had that many words for snow, did we? If you start actually thinking about snow in all of its forms you can imagine that there are an awful lot of words about it. Just in our immediate language we have words like hail, slush, sleet, settling… So this was a way to try and take it into a more imaginative world. And I really wanted Stephen to read this because I wanted to have someone who had an incredibly beautiful voice but also someone with a real sense of authority when he said things. So the idea was that the words would get progressively more silly really but even when they were silly there was this idea that they would have been important, to still carry weight. And I really, really wanted him to do it and it was fantastic that he could do it. (…) I just briefly explained to him the idea of the song, more or less what I said to you really. I just said it’s our idea of 50 Words For Snow. Stephen is a lovely man but he is also an extraordinary person and an incredible actor amongst his many other talents. So really it was just trying to get the right tone which was the only thing we had to work on. He just came into the studio and we just worked through the words. And he works very quickly because he’s such an able performer. (…) I think faloop’njoompoola is one of my favourites. [laughs]

John Doran, ‘A Demon In The Drift: Kate Bush Interviewed‘. The Quietus, 2011” – Kate Bush Encyclopedia

“The title track is the highlight and possibly the most baffling piece of music to be heard all year. Stephen Fry is an unusual choice of guest as he intones 50 different synonyms for snow over a dense tribal backing. These terms for snow are mostly made up, and go from the beautiful (‘blackbird braille’), to the ridiculous (‘Boomerangablanca’). A lot of thought has clearly gone into these linguistic creations and a read of the lyric sheet is strongly recommended. It is an utterly bonkers piece but it encapsulates everything that is so unique and fascinating about Bush” – DIY

“Among Angels’ is a song written by Kate Bush. It was originally released on her tenth studio album 50 Words For Snow in 2011.

Versions

There is only one studio version of this song.

A live version appears on the album Before The Dawn.

Performances

The song was performed live as the last encore on Kate’s Before The Dawn shows in London, 2014.

Cover versions

‘Among Angels’ was covered by Grimeland.

Lyrics

Only you can do something about it

There’s no-one there, my friend, any better

I might know what you mean when you say you fall apart

Aren’t we all the same? In and out of doubt

I can see angels standing around you

They shimmer like mirrors in Summer

But you don’t know it

And they will carry you o’er the walls

If you need us, just call

Rest your weary world in their hands

Lay your broken laugh at their feet

I can see angels around you

They shimmer like mirrors in summer

There’s someone who’s loved you forever but you don’t know it

You might feel it and just not show it” – Kate Bush Encyclopedia

THREE: Hounds of Love (1985): Hello Earth/The Morning Fog

“‘Hello Earth’ was a very difficult track to write, as well, because it was… in some ways it was too big for me. [Laughs] And I ended up with this song that had two huge great holes in the choruses, where the drums stopped, and everything stopped, and people would say to me, “what’s going to happen in these choruses,” and I hadn’t got a clue.

We had the whole song, it was all there, but these huge, great holes in the choruses. And I knew I wanted to put something in there, and I’d had this idea to put a vocal piece in there, that was like this traditional tune I’d heard used in the film Nosferatu. And really everything I came up with, it with was rubbish really compared to what this piece was saying. So we did some research to find out if it was possible to use it. And it was, so that’s what we did, we re-recorded the piece and I kind of made up words that sounded like what I could hear was happening on the original. And suddenly there was these beautiful voices in these chorus that had just been like two black holes.

In some ways I thought of it as a lullaby for the Earth. And it was the idea of turning the whole thing upside down and looking at it from completely above. You know, that image of if you were lying in water at night and you were looking up at the sky all the time, I wonder if you wouldn’t get the sense of as the stars were reflected in the water, you know, a sense of like, you could be looking up at water that’s reflecting the stars from the sky that you’re in. And the idea of them looking down at the earth and seeing these storms forming over America and moving around the globe, and they have this like huge fantasticly overseeing view of everything, everything is in total perspective. And way, way down there somewhere there’s this little dot in the ocean that is them - Richard Skinner, ‘Classic Albums interview: Hounds Of Love. Radio 1 (UK), aired 26 January 1992” – Kate Bush Encyclopedia

“Well, that’s really meant to be the rescue of the whole situation, where now suddenly out of all this darkness and weight comes light. You know, the weightiness is gone and here’s the morning, and it’s meant to feel very positive and bright and uplifting from the rest of dense, darkness of the previous track. And although it doesn’t say so, in my mind this was the song where they were rescued, where they get pulled out of the water. And it’s very much a song of seeing perspective, of really, you know, of being so grateful for everything that you have, that you’re never grateful of in ordinary life because you just abuse it totally. And it was also meant to be one of those kind of “thank you and goodnight” songs. You know, the little finale where everyone does a little dance and then the bow and then they leave the stage. [laughs] - Richard Skinner, ‘Classic Albums interview: Hounds Of Love. Radio 1 (UK), aired 26 January 1992 – Kate Bush Encyclopedia

TWO: Never for Ever (1980): Army Dreamers/Breathing

“Since we’re used to Bush being asleep to political infrastructure and class, we can at least turn to her complex politics of domesticity. While she doesn’t interrogate the structural causes of political violence, she’s still centering a song around the vulnerable people whose lives are destroyed by it. Never for Ever is populated by mothers and wives. Five of its eleven songs explicitly focus on maternal and uxorial figures, and that’s if we don’t count the broadly familial “All We Ever Look For.” Bush’s wives and mothers tend towards fatigue over their familial roles, experiencing emotions that contradict their outward actions or social operations. Bush’s mothers are an intrinsic good whose absence or loss is a tragedy, and whose losses are a social catastrophe. Key to the mother’s characterization in “Army Dreamers” is absence. She bemoans not merely her lost son, but his lost opportunities and the things she couldn’t provide for him. “What a waste of army dreamers,” muses Bush, in a ritual mourning of military casualties, which treats them as a cessation of dreams.

Most impressive is the way “Army Dreamers” treats the mother as an individual while also stressing her importance to her family. Stripped of her duties to her son, she is left with no more motherhood to perform. This suggests that while war is horrible, the people who are left behind have their own experiences of it. Men get sent off to die, and the women they leave behind are expected to grieve dutifully. Yet they’re prescribed a performative kind of grief — the actual effects of trauma are widely besmirched and ignored by the jingoistic reactionaries who send civilians off to die. Women are usually seen as broken when their soldiers fail to come home — this isn’t quite what Bush does. Is the mother broken? No, of course not. Has she had a vital part of her life snatched from her? Utterly.

There’s a touch of sentimentalism to this, if at least a grounded and humanitarian one. Violent deaths are often devastating because they cut short the lives of unsuspecting civilians who’ve been planning to go live their lives as usual the next day. Bush’s anti-militarism is hardly strident, but “Army Dreamers” has an edge to it even in its understatedness, blaming the services of “B.F.P.O” for overseas tragedies (although interestingly, her son’s death appears to be an accident — there’s little fanfare of death, no suggestion of the glory of battle). The horror of the death is largely its silence — all the things that couldn’t happen, no matter how much saying them would make them so.

The politics of the situation are left understated, as is typical for Bush, and yet with a light inimical rage, as if Bush is finally turning to the British establishment and shouting “look at what you’ve done!” While “Army Dreamers” is far from an indictment of the military-industrial complex (indeed, it has more to do with the British Army’s consumption of Irish civilians than anything else), its highlighting of war as futile is striking. “Give the kid the pick of pips/and give him all your stripes and ribbons/now he’s sitting in his hole/he might as well have buttons and bows” is a line of understated condemnation that spits on military emblems (pips are a British Army insignia) and consolidates trenches and graves. “B. F. P. O.,,” intone Bush’s backing vocalists again and again. In interviews, Bush backpedals from any perceived anti-militarist sentiments in her work (“I’m not slagging off the army…”), but her song tells a different story: nothing comes with B. F. P. O. except carnage” – Dreams of Orgonon

“It’s about a baby still in the mother’s womb at the time of a nuclear fallout, but it’s more of a spiritual being. It has all its senses: sight, smell, touch, taste and hearing, and it knows what is going on outside the mother’s womb, and yet it wants desperately to carry on living, as we all do of course. Nuclear fallout is something we’re all aware of, and worried about happening in our lives, and it’s something we should all take time to think about. We’re all innocent, none of us deserve to be blown up - Deanne Pearson, ‘The Me Inside’. Smash Hits (UK), May 1980

When I wrote the song, it was from such a personal viewpoint. It was just through having heard a thing for years without it ever having got through to me. ‘Til the moment it hit me, I hadn’t really been moved. Then I suddenly realised the whole devastation and disgusting arrogance of it all. Trying to destroy something that we’ve not created – the earth. The only thing we are is a breathing mechanism: everything is breathing. Without it we’re just nothing. All we’ve got is our lives, and I was worried that when people heard it they were going to think, ‘She’s exploiting commercially this terribly real thing.’ I was very worried that people weren’t going to take me from my emotional standpoint rather than the commercial one. But they did, which is great. I was worried that people wouldn’t want to worry about it because it’s so real. I was also worried that it was too negative, but I do feel that there is hope in the whole thing, just for the fact that it’s a message from the future. It’s not from now, it’s from a spirit that may exist in the future, a non-existent spiritual embryo who sees all and who’s been round time and time again so they know what the world’s all about. This time they don’t want to come out, because they know they’re not going to live. It’s almost like the mother’s stomach is a big window that’s like a cinema screen, and they’re seeing all this terrible chaos - Kris Needs, ‘Fire In The Bush’. Zigzag (UK), 1980” – Kate Bush Encyclopedia

ONE: The Dreaming (1982): Houdini/Get Out of My House

“Houdini” is the face of The Dreaming. It’s one of the only Bush sleeves where the image is supplied by the song. Its aspect, another creation of fraternal mainstay John Carder Bush, is a sepia photograph in medium closeup depicting a slightly agrestal Bush with her head tilted to the right, with her mouth open wide revealing a key on her tongue, which she passes to a faceless Del Palmer. This image derives from the lyrics of “Houdini,” which impart the fictionalized yet broadly historical experience of Bess Houdini, widow of premier escapologist Harry Houdini, who tries to contact her late husband through necromancy (“I wait at the table/hold hands with weeping strangers/wait for you/to join the group”). The relevant lyric “with a kiss I’d pass the key/and feel your tongue, teasing and receiving,” is unique among pop lyrics, as the overwhelming majority of them don’t contain idle recollections of Frenching a deceased spouse. It’s a bald-faced and ostentatiously move that flags how uninterested in notions of “normality” Bush is.

This furthermore indicates the subversive narratology Bush is pursuing. It’s quite boldly literal in the Carder Bush photo, where Del Palmer’s face is turned away from the frame. There’s an occlusion of “great man” narratives to “Houdini.” It’s named after one of the 20th century’s great performers, but it’s largely defined by his absence. As a result, the story has to be about the widowed Bess and her grief. Impressively, “Houdini” avoids elegy for the accomplishments of a Great Man, opting instead for the love Bess Houdini bore for her husband and the ecstatically weird lengths she went to demonstrate that.

The song is far from a stringent one. “Houdini” is fueled by anguished conniptions rather than melodic coherence. The verse initially sounds like “The Infant Kiss” or some other perfectly normal song with its piano balladry in Eb minor with a progression that finishes on a major tonic chord. It commences as a séance with mourners preparing to reach into the ether (“the tambourine jingle-jangles/the medium roams and rambles”). The refrain is the apex of Bush shrieks, culminating in a gravely, agonized “WITH YOUR LIFE/THE ONLY THING IN MY MIND/WE PULL YOU FROM THE WATER!” The result is hardly melodic — it’s willfully ugly, produced by Bush eating lots of chocolate and drinking milk to sabotage her own voice. Whether or not the experiment works, it doesn’t seem like Bush cares — she wants this to sound raw and ugly” – Dreams of Orgonon

“Uncertainty pervades “Get Out of My House,” The Dreaming’s brutal culmination. Catalyzed by its beleaguering yet urgent drumbeat and a lacerating lead guitar part from Alan Murphy, it is confrontational and purgative in its spectacular vocal menagerie, all in dialogue (often call-and-response) with one another yet seemingly not of an accord, as the bombastic and tremulous delivery of “when you left, the door was…” is answered by the siren-like, low-mixed B.V.’s crying “SLAMMING!” Adhering mostly to 4/4, “Get Out of My House” revolves through dizzying sequences of repetitive chord changes, with its first verse in G# melodic minor, confined to a progression of i-IV (G# minor – C#), moving to the natural minor in Verse Two with a progression of i-iv (G# minor – C # minor), signaling a domination of brutal repetition and minor keys without catharsis. With one of Bush’s most agonized vocals carrying the refrain (a genuinely harrowing and throaty “GET OUT OF MY HOUSE!”), the song emits agony, trauma, and expulsion.

***

The man who was my father often pontificated about his love for me. Shedding the crocodile tears of a consummate sentimentalist, he would frequently expatiate about how proud he was of me and what a good person I was. This would inevitably happen after he mocked me for my everyday behavior, berated me for having opinions contradictory to his own, treat himself as an authority talking down to a stupid and helpless buffoon, call me a prick, and shooting down pretty much every attempt I made to be my own person. Such is paternalism masquerading as parenting.

In the latter half of 2017, as I was inching away from the upbringing I’d endured and the boy I once was, I was bundled up in my then-father’s living room, watched The Shining for the fifth or seventh or tenth time. I was intimately familiar with the movie, but something felt different this time. I was emotionally attuned to the nuances of Shelley Duvall and Jack Nicholson’s performances that went beyond visual literacy. The scene that deeply impacted me this time around was Jack’s one scene alone with Danny. It is loveless, leering, and utterly terrifying. “You know I’d never hurt you, don’t you?” says Jack to the child whose arm he broke three years ago. It is not a question, but at once a lie and a threat. Jack clearly means “You’d BETTER know that.” I shuddered, and for the first time I wept over a horror movie. In the tepid comfort of my sperm donor’s living room, Jack Nicholson’s sneered declaration of love struck intimately close to home.

***

Stanley Kubrick’s film version of The Shining touches on intergenerational abuse, trauma, systemic violence, and spatiotemporal dyschronia more than Stephen King’s novel does. While King labors under the delusion that his story is about a broken alcoholic’s tragic descent into madness, Kubrick’s film presents washed-up writer, domestic abuser, alcoholic, and axe murderer Jack Torrance as a capricious, mean-minded, narcissistic, mendacious, gaslighting bastard. While King has railed against Kubrick for bowdlerizing Jack’s humanity, Kubrick and Jack Nicholson in fact make Jack a more rounded character. While Stephen King’s idea of characterization is two-dimensional (consisting of a crucial flaw and a noble virtue), Kubrick and his actors sketch character in terms of behavior and small gestures that reveal the nature of the Torrances. As a result, Jack’s smug maliciousness in the film is more psychologically choate than his counterpart in the book” - Dreams of Orgonon